There are many ways to experience the past. Some require long hallways and velvet ropes. Some require archival gloves and silence. And some require nothing more than a screen, a search bar, and a willingness to look at images people once flipped through without a thought.

The New Yorker cover is one of the best portals. It was never meant to last. It was topical, playful, made for the week of its release and then discarded. But what was once disposable becomes luminous in hindsight. A cover holds the rhythm of the everyday. It shows us what was funny, what was fashionable, what was assumed. And when you look at it now you feel the pulse of a time that thought it was ordinary.

Take the New Yorker cover from May 10, 1930 by Theodore G. Haupt .

Zeppelins and airplanes hover over New York’s skyline. In 1930 this was not quaint. It was thrilling. It was terrifying. Airships represented the possibility of speed and disaster at once. To imagine this cover as a story is to feel the suspense of the modern, the vertigo of new technology, the wonder of looking up and seeing the sky fill with engines.

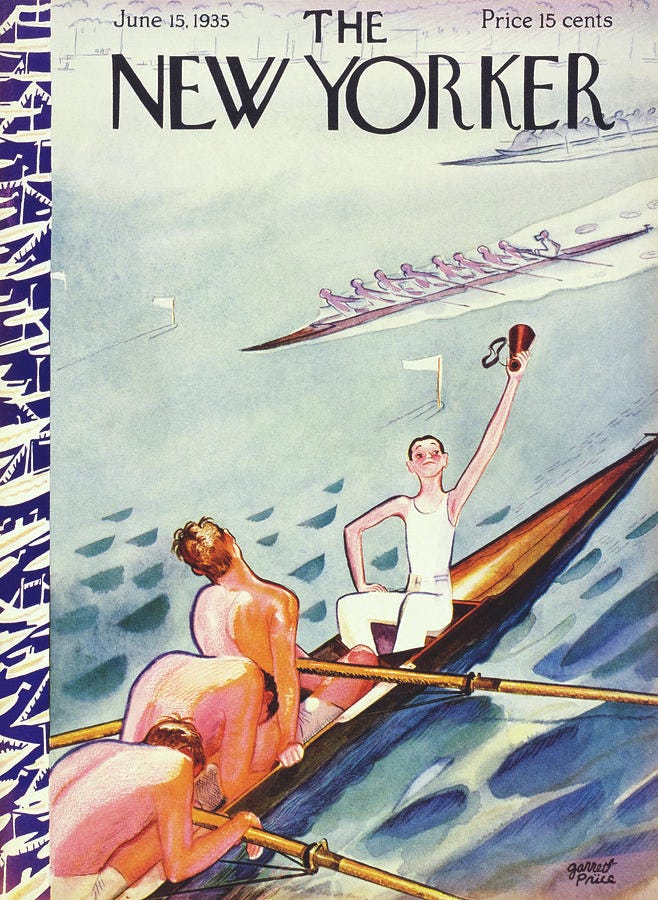

Now open the cover from June 15, 1935 by Garrett Price.

A rowing team collapses in exhaustion while their coxswain raises a limp arm in victory. The paint still glistens with sweat. Look at it long enough and you can almost hear the coxswain’s ragged voice, the summer heat pressing against the river, the pride that feels immense and fleeting at once. A week later, a new cover replaced it. But here it is again, suspended.

This is where the game begins. You do not stop at looking. You invent. A woman on a rooftop becomes the center of a love story. A dog gazing into a subway grate becomes a detective waiting for a signal. A rower with his head down becomes a boy wondering what to do with his life. None of these stories are true, and yet each one makes the past vivid. You make history not through accuracy but through attention.

It is easy to try. Pull up the digital archive, scroll, pick randomly. Take turns telling stories for the figures you see. Play for laughter, or for surprise, or for tenderness. Pair each decade with a drink to set the mood. Let the past sit with you in your living room, not as an artifact sealed in glass but as a guest invited to join the conversation.

Because history is not only in the preserved and the official. It is also in the scraps of the everyday. A cover made to be forgotten can become a museum object if you let it. A moment once considered ordinary can become extraordinary if you decide to look closely. And when you tell stories out of them, you are not just entertaining yourself. You are reminding history that it is alive.

Explore the full archive here: New Yorker Cover Archive

Most people no longer wish to think. They want it all explained in digestible and quick terms. That removes the need for artistic expression that is not literal or sensational.

Magazine covers from the 40s-60s I think had the catchiest artwork.